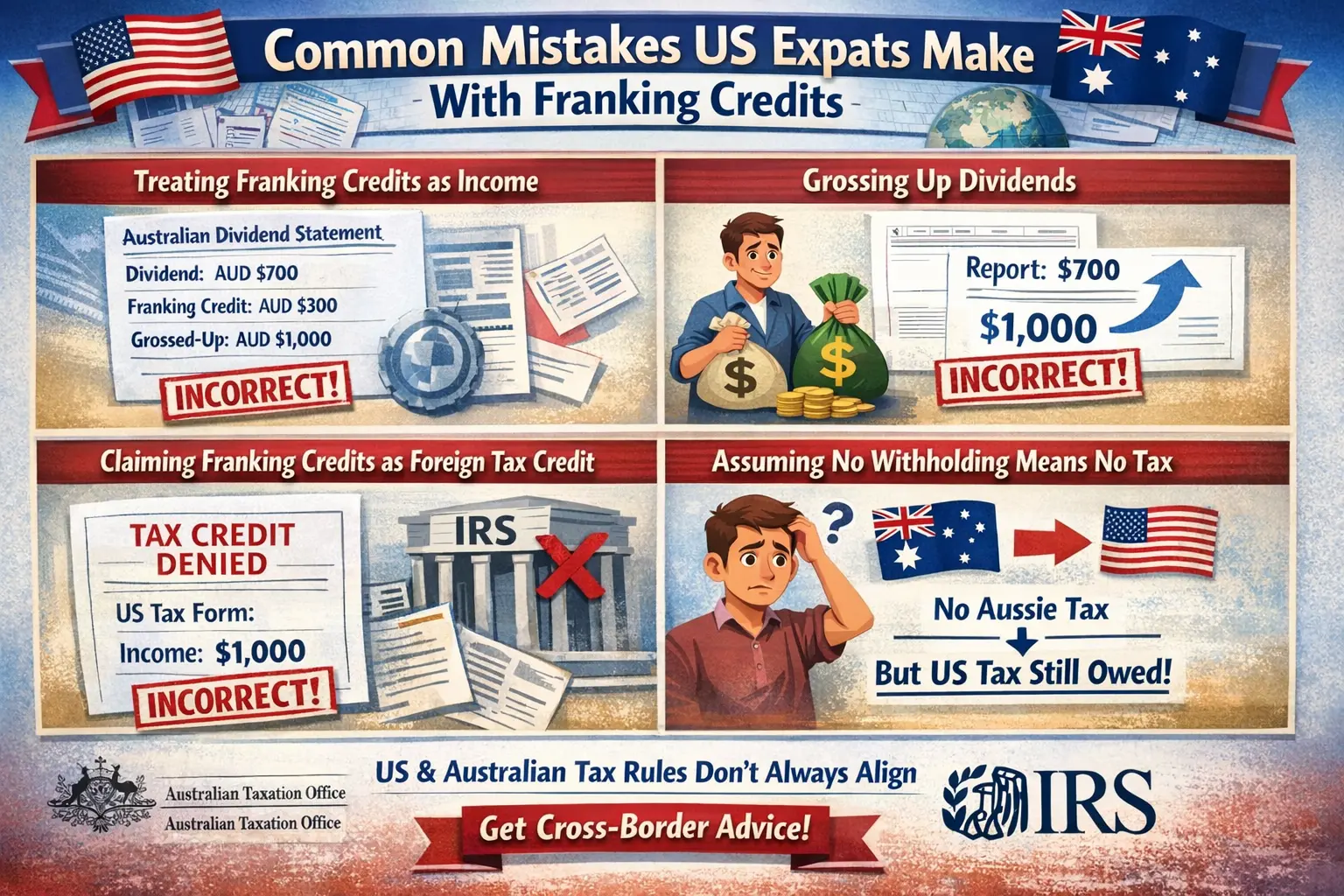

Common Mistakes US Expats Make With Franking Credits

Most of the franking-credit mistakes US expats make aren’t reckless. They’re reasonable. They come from looking at an Australian dividend statement, seeing several official-looking numbers, and trying to be careful on a US return that doesn’t leave much room for interpretation.

Still, those reasonable assumptions can drift into quiet errors. And because franking credits sit right at the seam between two tax systems, the mistakes tend to repeat themselves.

Treating franking credits as US-taxable income

This is the most common one, and it usually starts with good intentions.

An Australian dividend statement shows a cash amount, a franking credit, and a larger “grossed-up” figure. Faced with that, many US expats think, I’d rather over-report than under-report. So they include the franking credit as income on their US return.

From the US perspective, though, income is about what you actually receive or control. Franking credits aren’t cash. You can’t move them, spend them, or reinvest them. They exist as a tax attribute inside the Australian system. That’s why, under US rules, they aren’t treated as income at all.

Over-reporting may feel conservative, but it can inflate US tax unnecessarily.

Grossing up dividends because Australia does

Closely related, but slightly different, is the habit of grossing up US dividend income.

In Australia, the grossed-up dividend makes sense. It reflects company tax paid and aligns with how Australia calculates personal tax. On a US tax return, however, that gross-up doesn’t belong. The US doesn’t ask you to reconstruct corporate tax paid overseas when reporting personal dividend income.

If you received AUD 700 in cash, that’s the number the US cares about. The additional AUD 300 shown as a franking credit may be relevant locally, but it doesn’t change what you received as a shareholder.

Trying to claim franking credits as a Foreign Tax Credit

This mistake usually comes from a very logical leap: tax was paid, so I should be able to credit it.

The issue is who paid the tax. Under US Foreign Tax Credit rules, the credit generally applies only to foreign taxes imposed on you personally. Franking credits represent Australian company tax, not shareholder tax. Even though Australia lets shareholders benefit from that tax, the US doesn’t treat it as tax you paid.

This position is consistent with how the Internal Revenue Service frames creditable foreign taxes. The mismatch isn’t philosophical. It’s structural.

Assuming no withholding means no US tax

Fully franked dividends often come with no Australian withholding tax. That’s efficient from an Australian standpoint. For US expats, however, it can feel like a trap.

No withholding doesn’t mean no tax. It just means there’s no Australian tax imposed on you personally at the shareholder level. When the US taxes the dividend, there’s often no Foreign Tax Credit available to soften the result. That’s where the “double taxation” feeling comes from, even though both countries are applying their own rules correctly.

Focusing on franking credits while ignoring investment structure

It’s easy to obsess over franking percentages and credits while missing the bigger picture.

From a US point of view, the structure of the investment often matters more than the credit attached to it. Individual Australian shares are one thing. Australian managed funds, listed investment companies, and ETFs can introduce entirely different US tax and reporting consequences.

In many real-world cases, franking credits turn out to be the least consequential issue in the portfolio.

Assuming Australian advice automatically applies in the US

Australian tax advice is usually correct for Australia. The problem is assuming it travels intact across borders.

An Australian accountant may say, accurately, that the dividend has already been taxed or that franking credits prevent double taxation. That advice works inside the Australian system. It doesn’t automatically translate to US reporting, which follows different definitions and priorities.

This isn’t a failure of Australian advice. It’s a reminder that cross-border situations need a cross-border context.

Where Careful Planning Helps Avoid Surprises

Most franking-credit mistakes don’t come from cutting corners. They come from trying to reconcile two systems that weren’t designed to line up. The Australian Tax Office, represented by the Australian Taxation Office, and the IRS each apply internally consistent rules. The friction appears only when you live in both worlds at once.

Careful planning doesn’t always eliminate tax. What it does, far more reliably, is eliminate confusion. And for most US expats, fewer surprises at filing time are worth far more than chasing the perfect answer after the fact.

May Also Read: Expatriate vs. Expat: U.S. Tax Treatment Rules (New) 2026